Them’s Fightin’ Words

“Our life is shaped by our mind, for we become what we think.”

- Buddha

“No sympathy from me. Sorry not sorry.”

- A dude online

The humble destination of this article is the truism that we should all be nicer to each other, but maybe the scenery along the way will at least be interesting. We’ll begin in the obvious place: rat studies from the 1980s.

In 1985 or thereabouts, animal researcher Ken Cheng began running experiments on the spatial behavior of rats, because TikTok did not exist and he needed some other outlet for his lifeforce. First, he put a rat in the center of a rectangular white room devoid of visual cues the rat could use to orient itself (except for the long walls of the room). Then, he allowed the rat to see a treat being hidden behind one of the panels he had installed in the corners of the room. Finally, he spun the rat around a bunch to disorient it (I’m imagining a swinging-by-the-tail situation, but it might have been more humane), and set it loose to find the treat.

When he released the rat, it would always use the long walls to optimize its chance of going the right direction, but beyond that it was clearly guessing: the first-try success rate was 50%.

Cheng’s next bright idea was to paint one of the walls blue. Rats can see colors, and they can pass left-right orientation tests with ease, so Cheng thought the rat might be able to eliminate all errors by marking the relative position of the treat and the blue wall. He was disappointed (or maybe elated—it’s hard to say what makes a rat person happy) when the success rate remained at 50%. It was as if the rat could not even take the blue wall into account.

A decade later, Harvard psychologist Elizabeth Spelke repeated this experiment with human babies. Some features of her study were different from the original’s—she didn’t test the babies with food, for example, and because they lacked tails she had to shake them vigorously to disorient them (just kidding)—but in all salient ways the process was the same.

Surely, she thought, an 18-month-old child will outperform a rodent, but NO! The babies couldn’t find the object they were looking for more than half the time on the first try, even with a painted wall to guide them. She started bringing in older and older children, three-year-olds, four-year-olds, and got the same result. But when she brought in children around six years old, suddenly they began to pass the test as consistently as you would expect a human adult to do.

Why the change?

As the delightful Radiolab episode that inspired this article explains, around age six, a typical English-speaking human being begins to use function words skillfully. They might use the prepositions to, from, and of to express complex spatial relationships such as “left of the blue wall.” Before that, while the concepts “blue wall,” “left,” and even “of” might be understood one at a time, they do not merge. They are stars in a foreign sky, patternless, separate, adding up to nothing beyond themselves. Spelke’s hypothesis is that the surge in language development around age six allows links to form between previously isolated concepts, as if a chart of constellations were being drawn in the child’s mind. This, she says, may explain the difference in outcomes for four-year-olds and six-year-olds in her experiment.

The implications are strange. We often make a tacit assumption that language and perception are mostly distinct. It seems like two people with different levels of language development should look at a room and see the same thing. After all, they both have human vision—light in the room enters their eyes almost identically and is converted to near-identical electrical signals in their brain, regardless of the words they do or do not share.

But, if Spelke’s hypothesis is correct, there is some interrelation between verbal and sensory networks deep enough to change our fundamental interpretations of the sensory signals our brains take in. A four-year-old sees only a scattering of information, a general…something. A six-year-old sees the object left of the blue wall. Maybe we aren’t even able to perceive a sensory stimulus clearly until we have a word for every part of it, or words for a similar stimulus.

There are other examples of this hypothesis in other arenas. At least one classical scholar has discussed the repeated mention of the “wine-dark sea” in Homer’s Odyssey as a consequence of the fact that Homer’s language lacked a word for the color blue. People in ancient Greece, the argument goes, described colors by luminance, not hue, and therefore to them a dark blue might as well have been a dark red.

One wonders: did they look out at the sea and say, “Someday, we’ll need a new word for that color, because it is clearly different from wine, but for now it’s fine, because the Peloponnesian War is about to kick off and we need to go find our athletic sandals”? Or did they look out at the sea and find it indistinguishable from wine, until the day that the concept of blue, along with a name for it, arose spontaneously in their minds or was embedded by an external agent?

Do you use words because you are smarter than a rat, or are you smarter than a rat because you use words? Weird stuff.

To be sure, there’s a lot of doubt hovering around these linguistic-cognitive phenomena. It would probably be an overstatement to declare from the available evidence that changes in language cause changes in perception, period. Perhaps some uncontrolled variable skewed the results of Cheng’s study, for example. Maybe, at random, he selected rats with a greater drive to explore every corner of a new space than to seek food, and if he had simply used rats without that quirk they would have passed his test 100% of the time. Maybe Spelke selected three-year-olds whose brains go wonky under indoor lights for some reason. Maybe her conclusion was backward: maybe the machinery of perception achieves full power at age six, but not before, and that drives the increase in language proficiency, rather than vice versa. If we could somehow get our hands on a human adult who had lived their whole life on a deserted island and never heard a word of any language, would they be able to navigate the white room? Etc.

Nonetheless, there is at least cause to suspect that the words we use and the way we see the world are much more closely related than we realize as we go about our lives.

The Here and Now

Accepting the intertwining of language and perception, we may find ourselves a teensy bit troubled by patterns of modern public discourse, much of which occurs online. There are exceptions, obviously, but online discussions tend to reward certainty, force, fluency, and ruthlessness. Eloquence for its own sake seems to have become the core of our communication: the substance of what you say doesn’t matter, only that you say it with confidence, without hesitation, and in a pleasant rhythm or with grammatical symmetry (e.g., “If you can’t love me at my worst, you don’t deserve me at my best”).

Examples abound.

Was this probably true of all human communication for all time? Yes. But our online habits of expression appear to be sharpening our worst impulses to a spear point. In general, it’s easier to deride or condemn someone when they’re not in the room with you and there’s no chance of physical violence breaking out. As we become accustomed to the cadence of combative language, it seems reasonable to wonder whether it will take over our minds, bit by bit, and eventually determine our behavior not only in digital settings but also in the real world.

If we do not cultivate habits of forbearance, of accepting nuance, of accepting the physical discomfort that comes from pauses and disagreements, and instead embrace reactivity, certitude, and the zest of the perfect insult, who do we become?

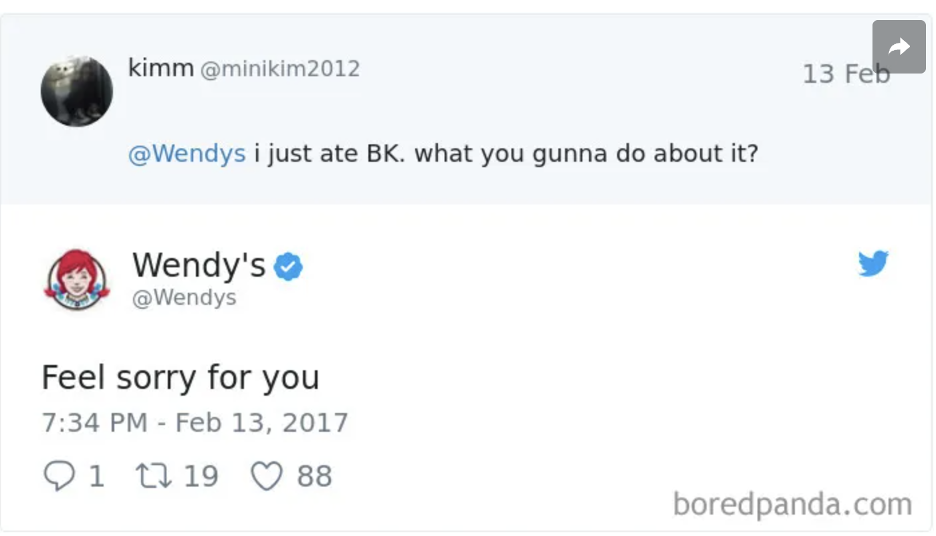

Marketing is not untouched by these trends, by the way.

A sick Wendy’s Twitter burn is perhaps akin to Wendy’s food: it feels fantastic to consume in the moment, but if you consume it too often, without other content to offset its deficiencies and mitigate its harms, it will probably cause problems sooner or later. If we believe that words shape reality, we should acknowledge that they will at some level shape how we see each other. Much as a rat can pick either the right way or the wrong way to get to a treat, we may have only a binary choice available to us in any moment of verbal expression: to travel on the love pathway or the hate pathway.

There is a specter haunting the relationship between language and perception: the possibility that—by pickling in a sea of fighting words for too long without moderation, caution, or even basic awareness—we will turn into hateful people by increments, sorting larger and larger swaths of humanity into the Irredeemable Garbage pile, and the whole time believe ourselves to be as righteous and compassionate as ever.